Mazel Tov

Walter Benjamin #5: "Zur Astrologie"

In his 1933 essay “Agesilaus Santander,” Walter Benjamin identified himself as one “born under the sign of Saturn.”1

From this metaphysical assertion of Benjamin’s, the literary critic Susan Sontag (1933–2004) chose the name of the titular essay in her 1981 book Under the Sign of Saturn.

Sontag’s essay “Under the Sign of Saturn” affirms Walter Benjamin’s saturnine disposition, its stated intention being to “use the work to interpret the life,” to appreciate the personality Walter Benjamin possessed by investigating what he chose to write about. Sontag says:

He thought of himself as a melancholic, disdaining modern psychological labels and invoking the traditional astrological one: “I came into the world under the sign of Saturn— the star of slowest revolution, the planet of detours and delays.”

His major projects… cannot be fully understood unless one grasps how much they rely on a theory of melancholy. Benjamin projected himself, his temperament, into all his major subjects, and his temperament determined what he chose to write about. … Information that disclosed the melancholic, the solitary…

The influence of Saturn makes people “apathetic, indecisive, slow,” he writes in The Origin of German Trauerspiel (1928). Slowness is one characteristic of the melancholic temperament.2

Benjamin’s choice of phrasing for that bit of autobiographical trivia is curious. Two zodiac signs (Capricorn or Aquarius), not just one, are known to the astrologers as signs of Saturn, making the sign of Saturn an ambiguous descriptor. As we shall see, Benjamin’s knowledge of the zodiac makes oversight an unlikely explanation.

A similar phrase appears in one of the primary sources of Jewish mysticism:

One who was born under the influence of Saturn will be a man whose thoughts are for naught. And some say that everything that others think about him and plan to do to him is for naught.3

Could a reading of this tractate have inspired Benjamin to identify with the planet Saturn? Benjamin’s self-diagnosis of “under the sign of Saturn” might refer to his reading of a specific hour-of-the-day condition or a specific day-of-the-week condition from his own horoscope. Neither is it out of the question that a Saturnine affiliation was simply a self-selected personality trait he found apt.

Debates over how to determine a person’s predominating planetary influence led one of the authors of that Mishnah-period tractate to record this clarification:

It is not the constellation of the day of the week that determines a person’s nature; rather, it is the constellation of the hour that determines his nature.4

Gershom Scholem (1897–1982) may have dropped a hint as to which of these affiliations Benjamin had in mind in his biography of Walter Benjamin, where he summarizes a conversation at a Parisian café from the summer of 1927:

Benjamin was the first person I told about a very surprising discovery I had made: Sabbatian theology—that is, a messianic antinomianism that had developed within Judaism in strictly Jewish concepts. This discovery, which I made in the manuscripts of the British Museum and the Bodleian Library at Oxford, later led to very extensive research on my part.5

Scholem was disclosing his early research into the historical figure of Sabbatai Tsevi (1626–1676), whom Levantine and European Jews heralded as the promised messiah of eschatological expectation during the years 1665 and 1666 (a hope that Tsevi would himself smash upon his eventual conversion to Islam). The celebrity-mystic Sabbatai Tsevi bore the Hebrew name for the planet Saturn (Sabbatai). Later in 1957, Scholem would publish a thousand-page book on the life and times of Sabbatai Tsevi, the Ottoman-era messiah-claimant. Whether or not this post-medieval messianic fervor arrived at a saturnine fate, Scholem explained its founder’s name as one that wasn’t unusual for its time. “Children born on a Sabbath,” writes Scholem in his biography of Tsevi, “were frequently called Sabbatai.”6 Walter Benjamin, too, was born on the Sabbath; the fifteenth of July in 1892 was a Friday, and Benjamin was born after sunset.

So, it’s probable that when Benjamin wrote of being born under the sign of Saturn, he meant the day-of-the-week of his birth, the Sabbath.

To return to Benjamin’s “Agesilaus Santander,” that essay’s opening sentence discloses a mysterious assumption made by the parents of baby Walter:

When I was born, it occurred to my parents that I might perhaps become a writer.7

Benjamin does not elaborate on how such new parents (Walter was their firstborn) arrived at this conclusion before external signs of personality or predilections for language could have become developmentally apparent.

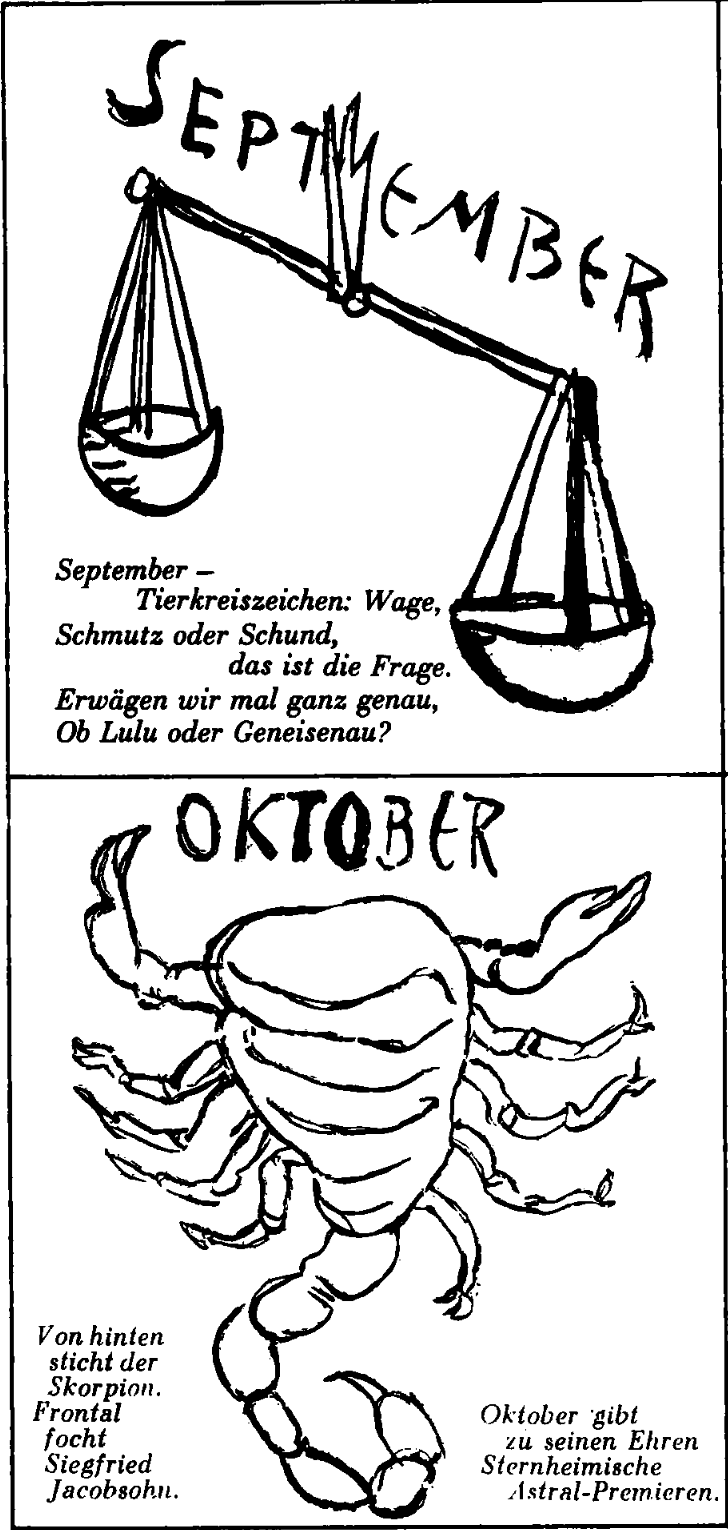

A 1927 wall calendar put out by the literary periodical Die Literarischen Welt (The Literary World) included a dozen short poems by Walter Benjamin naming the zodiac sign through which the sun traveled that month.

Here’s an example:

Januar

Es kündet das Jahr siebenundzwanzig

In Nord und Süd (und Freistaat Danzig)

Sich deutschen Leser günstig an

Im Tierkreiszeichen: Wassermann.8

My translation:

January

Thus heralds the year twenty-seven

In North and South (and the free state of Danzig)

For German readers auspicious

In the zodiac sign: Aquarius.

Illustrations by the painter Rudolf Großmann accompanied Walter Benjamin’s verses. Direct representational art in a pen-and-ink line style depicted that month’s constellation symbol, foregoing supplementary visual information. Take for example the drawings below showing Libra and Scorpio.

Walter Benjamin unpacked his interest in astrology in a 1932 essay “On Astrology,” which during his lifetime remained unpublished. Benjamin begins it by disavowing any “doctrine of magical ‘influences,’ or ‘radiant energies’ and so on.”9 In outlining his “complete prolegomenon of every rational astrology,” Benjamin avoids scientific positivism’s major objection to astrology. He grants validity to those measurements observing the vastness of the gulf between Earth and the stars; such distances prohibit the possibility of any influence from physical forces like gravity.

For Benjamin, if any similarities come into focus through the lens of astrology, such discoveries must be subject to our understanding of the practices of “people in Antiquity.”10 The use of astrology for fortune-telling and for personality categorization were common cultural practices in the Egyptian and Babylonian empires, including among the minority peoples dwelling in exile under their administration.

The absence of bleeding-edge research in academic departments of astrology meant to Benjamin that all modern books on reading the stars only regurgitated heuristics of old. These age-old associations, useful perhaps to the stargazers of extinct kingdoms, now miss the social context of the epochs during which their intended practitioners lived. Benjamin explains:

As students of ancient traditions, we have to reckon with the possibility that manifest configurations, mimetic resemblances, may once have existed where today we are no longer in a position even to guess at them.11

The planets do, for Benjamin, have distinct characters or essences (the German Wesen is his word, which also could mean “natures” or even “souls”).

Benjamin theorizes that when someone in primeval times accomplished a deed with certain characteristics, that later, when a celestial body reentered its former constellation from that prior time, some cultural memory of the earlier deed would be recollected (somehow) by that person’s successors, a memory not in the stars but in the deed done at such-and-such an hour. His words:

We must reckon with the fact that, in principle, events in the heavens could be imitated by people in former ages, whether as individuals or groups. Indeed, this imitation may be seen as the only authority that gave to astrology the character of experience. Modern man can be touched by a pale shadow of this on southern moonlit nights in which he feels, alive within himself, mimetic forces that he had thought long since dead, while nature, which possesses them all, transforms itself to resemble the moon.12

Other essays of Benjamin’s expand further on that “mimetic force” to mean the creative power to imitate, with human language being his primary example of such a mimetic force. Consciously or unconsciously, man must imitate in order to act in the world at all. Benjamin’s theory of astrological mimesis, then, must be one where temporal similarities reappear each time the conditions of an action’s collective history reemerge. Such memory recall, if it does take place, seems to demand of the unconscious significant operational capabilities.

The last paragraph of “On the Concept of History,” (1940) wraps up Benjamin’s final essay by comparing the religious view of time with that of the “soothsayers who queried time and learned what it had in store.”13 Benjamin contrasts such anxious curiosity against a different approach to the unknowable future:

We know that the Jews were prohibited from inquiring into the future: the Torah and the prayers instructed them in remembrance.14

That essay, “On the Concept of History,” sets its tone with an initial paragraph welcoming theology into the toolchest of political apparatus. If religious concepts can work as handy tools for the dissection of contemporary social issues, then the original theological principle being cited must be worth understanding:

What’s this prohibition against inquiring into the future?

One source for this restriction in the Torah (there are multiple) commands:

You shall not practice divination or soothsaying.15

The prolific Biblical commentator Rashi (1040–1105) provides some examples of both these practices. Rituals recognized as forbidden divination include:

drawing prognostications from the cry of a weasel

or the twittering of birds

or from the fact that the bread falls from his mouth16

or that a stag crosses his path

Rashi defines soothsaying as believing like “one [who] would say, ‘Such and such a day is auspicious to begin your work,’ or, ‘Such and such an hour is unlucky to embark [on a journey].’”17

So making decisions based on animal behaviors is right out. Fine. But what about the behaviors of the celestial spheres?

Biblical legend holds that Abraham the Patriarch was an astrologer so masterfully capable that distant princes sought out his skill at reading the heavens. Abraham would weep when he dwelt upon his own horoscope, crying out:

‘Master of the Universe, I looked at my astrological map, and according to the configuration of my constellations I am not fit to have a son.’ The Holy One, Blessed be He, said to him: ‘Emerge from your astrology’ (as the verse states: ‘And He brought him outside’)… ‘What is your thinking? Is it because Jupiter is situated in the west that you cannot have children? I will restore it and establish it in the east.’18

Despite the convincing astrological markers indicating otherwise, Abraham became the “father of many nations” through the numerous descendants of his sons Ishmael and Isaac. The Mishnah uses this hagiography to illustrate that prayer, holiness, and good deeds can overcome any predisposed tendencies a person may express. One’s mazel (birth-chart) may be overcome.

Another story from the same tractate illustrates further this concept of righteous deeds influencing a person’s life more powerfully than do the conditions of their birth:

Babylonian astrologers told Rav Naḥman bar Yitzḥak’s mother: Your son will be a thief. She did not allow him to uncover his head. She said to her son: Cover your head so that the fear of Heaven will be upon you, and pray for Divine mercy. He did not know why she said this to him. One day he was sitting and studying beneath a palm tree that did not belong to him, and the cloak fell off of his head. He lifted his eyes and saw the palm tree. He was overcome by impulse and he climbed up and detached a bunch of dates with his teeth. Apparently, he had an inborn inclination to steal, but was able to overcome that inclination with proper education and prayer.19

On the other hand, the philosopher of Jewish law Maimonides (1138–1204) strongly opposed the study of “astrology and the influence of the past and future conjunctions of the planets upon human affairs,”20 arguing that “accomplished scholars, whether they are religious or not, refuse to believe in the truth of this science. Its postulates can be refuted by real proofs on rational grounds.”21 Maimonides read the above-quoted negative commandment in the book of Leviticus as a prohibition against engaging in astrology.

In an apparent divergence from those Mishnah rulings which tolerated a degree of debate on astrological matters, Maimonides identified the entire field of study as “being the root of idolatry”22 Centuries before the scientific revolution, before Copernican heliocentrism, and before the aforementioned Sabbatian fervor, Maimonides forbade “paying any attention to the conjunctions of the stars.”

Walter Benjamin claimed to have been born under the sign of Saturn. For a literary calendar project, he wrote hymns to each of the twelve zodiac signs. He even composed a theory of how astrology might be real. Finally though, he taught of a Jewish prohibition against inquiring into the future.

If the alternative to prognostication is remembrance, can there be any role left for a semiotics of time in the language of celestial bodies? Benjamin’s advocacy for a “rational astrology” might be less centered in a dependence upon “expert” ability in divining the propriety of coming hours and more aligned with a contextualization of cultural histories into the temporal divisions of a planetary calendar.

But perhaps Benjamin’s “On the Concept of History” essay follows his previously held-beliefs not with an elaboration but with a modification. Does “On the Concept of History” confess to a change-of-heart on matters of astrological divination? Whereas a younger Benjamin defended “the poetic rapture of starry nights,”23 the elder man shared, in the final year of his life, the value he found in the ancestral prohibition against beliefs in lucky times.

Benjamin left his inheritors with insight into how memorializing the past “disenchanted the future, which holds sway over all those who turn to soothsayers for enlightenment.”24 Could it be that with these words Benjamin imitated the Biblical Abraham who “emerged from” his astrology-based worldview?

Walter Benjamin, “Agesilaus Santander (Second Version),” in Selected Writings Volume 2, Part 2: 1931-1934, edited by Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith, translated by Rodney Livingstone (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005), page 715.

Susan Sontag. “Under the Sign of Saturn.” Under the Sign of Saturn, (New York: Vintage Books, A Division of Random House, 1981), page 111.

Shabbat 156a, Koren-Steinsaltz translation. It’s known that Walter Benjamin knew almost no Hebrew, but he could have read this passage in a German translation, or it may have been brought to his attention by his friend Gershom Scholem, who wrote several books on Jewish mysticism (and dedicated one to Walter Benjamin).

Ibid.

Gershom Scholem, Walter Benjamin: The Story of a Friendship, translated by Harry Zohn (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1981), page 136.

Gershom Scholem, Sabbatai Ṣevi: The Mystical Messiah (1626-1676), translated by R. J. Zwi Werblowsky (Princeton: Bollingen Series XCIII, Princeton University Press, 2016), page 104.

Walter Benjamin, “Agesilaus Santander (Second Version),” in Selected Writings Volume 2, Part 2: 1931-1934, edited by Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith, translated by Rodney Livingstone (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005), page 714.

Walter Benjamin, “Wandkalender der Literarischen Welt für 1927,” in Walter Benjamin: Gesammelte Schriften, Band VI, edited by Rolf Tiedemann and Hermann Schweppenhäuser (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1991), page 546.

Walter Benjamin, “On Astrology,” in Selected Writings Volume 2, Part 2: 1931-1934, edited by Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith, translated by Rodney Livingstone (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005), page 684.

Ibid, page 685.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” in Selected Writings, Volume 4: 1938–1940, edited by Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, translated by Harry Zohn (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006), page 397.

Ibid.

Leviticus 19:26, JPS translation (2006).

The word “his” in the third given example refers back to the word “birds.” Cicero described the fortune-telling practice of watching bread fall from birds’ mouths in the book he completed in 44 BCE, De Divinatione, where he writes:

The sacred chickens, in eating the dough pellets thrown, must let some fall from their beaks. But according to the writings of your augurs, [a good omen] results if any of the food should fall to the ground.

M. Rosenbaum and A.M. Silbermann, Pentateuch with Targum Onkelos, Haphtaroth and Rashi’s Commentary, (New York: Hebrew Publishing Company, 1905), page 89a.

Tractate Shabbat (156a–156b, Koren-Steinsaltz translation).

Ibid, 156b.

Moses ben Maimon, from “Epistle to Yemen” in A Maimonides Reader, edited with introductions and notes by Isadore Twersky, (New York: Library of Jewish Studies, Behrman House, Inc.), page 452.

Ibid.

Moses ben Maimon, from “Letter on Astrology” in A Maimonides Reader, edited with introductions and notes by Isadore Twersky, (New York: Library of Jewish Studies, Behrman House, Inc.), page 465.

Walter Benjamin, “To the Planetarium,” (a chapter of One-Way Street) from Selected Writings, Volume 1: 1913–1926, edited by Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings, translated by Edmund Jephcott (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2004), page 486.

Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” in Selected Writings, Volume 4: 1938–1940, edited by Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, translated by Harry Zohn (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006), page 397.