“[I]s a twenty-year-old novel successful merely because it seems cleverly predictive or contains scenarios that feel ‘relevant’ to later audiences? If that were the mark of enduring fiction, Philip K. Dick would be the greatest novelist of all time.” [0]

Video game screenwriter Tom Bissell’s backhanded compliment to Philip K. Dick — in a forward written for another speculative novel, Infinite Jest — acknowledges that Philip K. Dick wrote novels at once clever, predictive, and relevant beyond their time; Dick’s stories, however, can lack a certain novelistic je ne sais quoi, he implies.

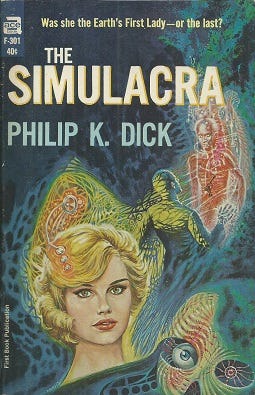

This book review of the 1964 science fiction novel The Simulacra by Philip K. Dick will attempt to situate The Simulacra in its historical context, in terms of the author’s apparent influences and in terms of the book’s subsequent influence, especially in philosophy. Philip K. Dick, in particular his novel The Simulacra, has made original and noteworthy contributions to a history of ideas that persists through contemporary discourse.

That title, though

The word simulacra (singular: simulacrum) appeared for the first time (as far as is known) in the Latin poem De Rerum Natura by Lucretius. Philip K. Dick esteemed this classical text so highly that he wrote a short story featuring it explicitly. Philip K. Dick’s short story “Not By Its Cover” first appeared in 1965, one year after The Simulacra [1]. “Not By Its Cover” contrasts Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura with Saint Paul’s first epistle to the Corinthians; in the short story, an intelligent Martian species finds a way to communicate its commentary on the two texts’ essentially irreconcilable claims about death and the afterlife.

Simulacra, as Lucretius defined them, were “likenesses or thin shapes… sent out from the surfaces of things” below the threshold of visible perception. These optical copies, in Lucretian physics, accounted for dreams, sexual fantasies, ghost visions, mythic creatures, imaginary visualization, and all manner of obscure visual phenomenon.

Saint Jerome, the main translator of the Latin Vulgate, was familiar enough with Lucretius to make claims about his life and his death that have remained unverified by later scholarship. Jerome (and those who assisted him translating the Bible into Latin) employed the word “simulacra,” or a conjugation thereof, a total of thirty-nine times.

In a sense, the word simulacra bridges an unexpected felicity between Lucretius and John the Evangelist. Lucretius believed that sexual imagery floated physically through the air and produced lust in men’s minds; thus, he wrote “It behooves one to flee from such images (simulacra)” [2]. The first Johannine epistle, translated from Koine Greek to Latin, used the same word to refer to graven images: “Children, keep yourselves from idols (simulacris)” [3]. Both passages, though demonstrating divergent definitions, find common ground in exhorting the avoidance of simulacra.

The word “simulacra” was used only sparsely in later Latin fiction by Virgil and other ancient authors. By the twentieth century, the word “simulacra” was rarely used in the English language. In particular, one could still find it in the writings of spiritist parapsychologists such as Gustave Géley [4], or the works of metaphysical poets such as William Butler Yeats (although he spelled it “simulacrae”) [5]. By the time Philip K. Dick wrote The Simulacra in March 1963, the most common place to find the word in print was in English-Latin dictionaries.

Philip K. Dick knew enough Latin to meditate at length on obscure Latin theological phrases in his later Exegesis. He had a habit of buttressing his book titles with Latinate words uncommon in lay English:

The Penultimate Truth

The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch

Deus Irae (collaboration with Roger Zelazny)

A. Lincoln, Simulacrum (not itself a book, but a magazine serial)

Like Lucretius, Philip K. Dick maintained a specific meaning for the word “simulacra” in the world of his book. Dick’s usage cleaves closer to the Vetus Testamentum usage of “graven images” than the phrase hit upon by most English translators of De Rerum Natura; one can speculate that Dick’s novel would doubtfully have produced the same impact had it been titled The Images of Things.

A stone rejected by its builder

Philip K. Dick’s biographer Lawrence Sutin wrote of The Simulacra “Of all Phil’s novel plots, this may be the most complex.” [6] The Simulacra has never been adapted for screen, stage, or video game console. Philip K. Dick published The Simulacra in 1964, the same year as three other of his novels:

The Penultimate Truth

Martian Time-Slip

Clans of the Alphane Moon.

Some of the themes from Dick’s other novels of this hyperprolific period of his career can seem to bleed together. As an example, The Penultimate Truth shares with The Simulacra the theme of a political leader whose facade of authentic humanity conceals a hidden elite who control the perception of leadership with technology. Although The Penultimate Truth reused the word simulacrum to describe this maneuver, the two stories imagined very different technologies accomplishing this effect.

Philip K. Dick mentioned The Simulacra in a 1978 journal entry examining themes spanning his fictional corpus:

Again and again, I attempt to formulate criteria for what is fake and what is not fake, in every area. From a comic book to a world leader to a girl friend to an entire universe. “Things are seldom what they seem” — right. It has to do with reality testing, which is related to another theme of mine: mental illness (which brings in hallucinations) and deliberate deception (The Penultimate Truth, The Simulacra, Game Players of Titan, etc., novels I usually overlook, and mental illness brings in Martian Time-Slip, Dr. Blood Money, The Simulacra, Clans. So virtually all of my writing interlocks at this substratum.). [7]

Alone in his central Venn diagram compartment, flanked on the left by mental illness novels and on the right by tales of deliberate deception, sits The Simulacra.

Philip K. Dick’s deprecation of The Simulacra (one of the “novels I usually overlook”) was also apparent in letters to his editor Terry Carr, to whom he wrote:

I’m f ———g overwhelmed by your shockingly favorable remarks about my writing. Just when I was beginning to think life had passed me by, too. Fancy. Well, God works in His wonderous [sic] ways, they say. However, what is “THE SIMULACRA”? Is that what I called FIRST LADY OF EARTH? I mean, Have I forgotten an entire novel? Wire instructions. Wire diagrams as to how to reassemble memory of forgotten novel. Or something. [8]

Philip K. Dick forgot (or simulated forgetting) that prior to the publication of The Simulacra, he had retitled his manuscript, replacing its earlier title First Lady of Earth.

Set and setting

The Simulacra partially situates its story in the shared space of a communal apartment building home. Apartments in The Simulacra have their own mandatory rituals and their own sets of laws: “communal apartment building codes.” Apartment life connotes status and attainment, representing liberation from the rough days of the youth work-homes. Like university dormitories, these group living communities imply mutual career or ideological interests. They also require periodic testing of their residents, ensuring a common baseline of civic knowledge. These buildings carry reputations: some have tens of thousands of residents, and are known to be newly erected with modern facilities. Other buildings bear age, dignity and exclusivity.

These group homes extend their life-impositions into a religious dimension, with mandatory building meetings that open uncomfortably with a guided prayer; rites of confession and contrition are facilitated for residents by means of a “confessomatic” (which, like all technology, has its share of maddening bugs).

The novel is set in the year 2041; for Philip K. Dick writing, this date was nearly eighty years in the future. While reading The Simulacra, I caught myself erroneously perceiving the book as an alternate history in the vein of Dick’s Hugo award-winner The Man in the High Castle. Make no mistake: there is no alternate history here.

When Dick wrote The Simulacra, all of the events forming the pivotal timeline of that world could still potentially have happened. The book’s timeline begins to diverge from the timeline that we in the twenty-first century call our real world history with the ascension to power of First Lady Nicole Thibodeaux, seventy-three years prior to the present-day of the novel. With some arithmetic, one can calculate this year as 1968, four years after the novel’s publication.

Neither do the acts of time-travel substantially differentiate the twentieth century history in the novel from the twentieth century history of its author. Time machines, called “von Lessinger equipment”, barely seem to affect events at all. Material changes which time travelers (“von Lessinger technicians”) achieve in the past are extinguished by opposing time travelers with opposite goals, who go back to the same past and ensure the operations of their time-traveling opponents somehow fail. Time travel is presented as a (disappointingly paradox-free) tool of the existing political order, and a tepid and feeble one at that.

The Simulacra is set in a future where the United States has apparently adopted a matriarchal mode of living. America has a charming First Lady whose tenure endures the vicissitudes of quadrennial elections. The perennial First Lady’s husband, no longer styled “President” in this future, but instead known as “der Alte”, is selected by general election every four years. His German-language title (meaning the old man or the old one), reflects this future’s unification of the United States of America and West Germany into a single state, abbreviated the USEA (United States of Europe and America).

Those residents of this world who want to explore the implications of this social structure on their state-of-mind and well-being in a professional setting face significant obstacles. In the opening chapter of the novel, a new law goes into effect banning the practice of psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysts across the country now face jail-time if any of their patients enter their clinics.

Characterization simulation

A criticism I have seen leveled against The Simulacra, that the story has too many characters only meagerly developed, isn’t totally meritless. This review can mention only a fractional subset of the novel’s dramatis personae.

The private lives of Philip K. Dick’s characters illustrate the society in which they live, and not the other way around. Romantic relationships — their joys, jealousies, quarrels, and vengeances — lack the high literary truth of emotional agony. Instead, Dick writes them sharply to illuminate the ways that human personal dynamics could be so very different from what we know.

In this matriarchal future, for example, we see a male record company employee (Nat Flieger) silently suffer humiliating sexual harassment from an unaccountable female executive (Molly Dondoldo). Elsewhere, two brothers ensnared in a love triangle (Chic Strikerock and Vince Strikerock) resign themselves with pacific grace and tact to the decision of the woman (Julie Applequist) who has dispassionately determined to leave her husband for her brother-in-law.

Society’s lower-class citizens and upper-class citizens alike (known as Bes and Ges respectively) adore their country’s First Lady, Nicole Thibodeaux. This woman’s preeminent position in the matriarchal political establishment rests on the public’s near-gravitational fetishization of her person.

Nicole’s talk-show-host-style leadership enchants her rapt United States citizens. Nightly broadcasts to the nation showcase her favorite curios and entertainers. The objects of her enjoyment become the subjects of pop quiz questionnaires required of citizens. Musical and artistic production for White House consumption has become the driving engine of the national economy.

The most sought-after entertainer in the country, Richard Kongrossian, plays piano by telekinetically striking the keys with his mind. The First Lady has sent her aids to hunt him down, as she has grown weary of the inferior musicianship her talent scouts present before her. A major record company has independently embarked on their own quest to find Richard Kongrossian, so they can record one last contractually-due album. Driven insane by the advertising machines of this future, the legendary Richard Kongrossian evades them all.

Advertising machines, called Theodorus Nitz commercials after their inventor, have the strength to enter a non-consenting moving vehicle, and the agility to evade gunshots from annoyed drivers. Kongrossian has so deeply internalized the marketing-jingles of these Nitz commercials that he anxiously believes his body to be the site of every intractable dilemma these ads describe to him. He self-soothes these anxieties by hospitalizing himself, and he considers taking far more drastic measures.

Plots of plots

Before Ace Books published The Simulacra in August 1964, Fantastic magazine published the short story “The Novelty Act” in its February 1964 edition, prefaced by this editorial summary:

If you carry to their illogical lengths the ideas of cooperative housing, culture-mania and amateur nights, you might begin to approximate the conditions under which the Brown brothers did their jug-playing music. [9]

By contrast, the jug musicians in The Simulacra are not brothers, and neither one is named Brown, but The Simulacra did keep salient the three ideas mentioned in that snippet. Philip K. Dick biographer Lawrence Sutin has suggested that the short story is a pared-down version of the novel, rather than the novel being an expansion of the short story [6].

Amongst so many subplots, the majority of which cannot be enumerated in this review, briefly examining “The Novelty Act” can allow us to infer what Philip K. Dick himself perhaps found to be the barest kernel of the novel’s plot.

For one, the short story retains the funniest part of The Simulacra, which is the jug musician subplot. A character named Ian Duncan excels at performing music on his glass jug. I fear any further summary of mine would destroy the situational humor, so I can only explain by sharing this excerpt from Chapter 2 of The Simulacra:

Going to the closet of his apartment, Ian Duncan bent down and carefully lifted a cloth-wrapped object into the light. We had so much youthful faith in this, he recalled. Tenderly, he unwrapped the jug; then, taking a deep breath, he blew a couple of hollow notes on it. Duncan & Miller and Their Two-man Jug Band, he and Al Miller had been, playing their own arrangement for two jugs of Bach and Mozart and Stravinsky. But the White House talent scout — — the skunk. He had never even given them a fair audition. It had been done, he told them. Jesse Pigg, the fabulous jug-artist from Alabama, had gotten to the White House first, entertaining and delighting the dozen and one members of the Thibodeaux family gathered there with his versions of “Derby Ram” and “John Henry” and the like.

“But,” Ian Duncan had protested, “this is classical jug. We play late Beethoven sonatas.”

“We’ll call you,” the talent scout had said briskly. [10]

The crisis moment in that narrative arc shows one of the musicians trembling in the cold, unsure of his whereabouts, after having his memory wiped by the government. This powerful image and its surrounding precedents and consequents is one that The Simulacra conveys with a sense of haunting relevancy.

The word “simulacra” is absent from the short story “The Novelty Act”, although it’s used seventeen times in the novel-body of The Simulacra.

The “simulacra” of The Simulacra are highly functional androids built to resemble human beings. The Ges, the informed upper-class, know full-well that the “husband” of Nicole Thibodeaux, their country’s der Alte, is non-human; that is, he is a robot simulating the human form: a simulacrum. Many of them work as ersatz engineers, helping to design and build the next planned simulacra. The construction of a der Alte (yes, the novel doubles the article) is a task requiring deft art, industrial facilities, and ruthless business cunning. When the country votes every four years to choose between two new husbands for Nicole, both candidates are simulacra.

Allusions supporting illusions

Philip K. Dick versed himself in a variety of intellectual fields ranging from sociology to film. The cross-pollinations from other disciplines into the niche genre of speculative fiction ground the unfamiliar universe Dick creates in a real culture, exposing the rich breadth of his stylistic influences. I compiled a list of references in The Simulacra which Philip K. Dick named (at least, those which I was able to identify):

Songs

“Chaconne in D” — Johann Sebastian Bach

“Fifth Unaccompanied Cello Suite” — Johann Sebastian Bach

“Goldberg Variations” — Johann Sebastian Bach

“Little Fugue in G Minor” — Johann Sebastian Bach

“Two Part Inventions” — Johann Sebastian Bach

“Stairway to the Stars” — Ella Fitzgerald

“Handel in the Strand” — Percy Grainger

“The Trout Quintet” — Franz Schubert

“Derby Ram” — Traditional folk song

“John Henry” — Traditional folk song

“Rock-a-bye My Sara Jane” — Traditional folk song

“Meistersinger” — Richard Wagner

“Parsifal” — Richard Wagner

“The Ring” — Richard Wagner

People

Aristotle (philosopher)

Ludwig van Beethoven (composer)

Ludwig Binswanger (psychologist)

Otto von Bismarck (politician)

Ernest Bloch (composer)

Martin Bormann (nazi)

Johannes Brahms (composer)

Paul Bunyan (lumberjack)

Aaron Copland (composer)

Adolf Eichmann (nazi)

Elizabeth I (monarch)

George III (monarch)

Joseph Goebbels (nazi)

Hermann Goering (nazi)

George Frideric Handel (composer)

Heinrich Himmler (nazi)

Adolph Hitler (nazi)

Jerome Kern (composer)

Jack Lemmon (actor)

Abraham Lincoln (president)

Shirley MacLaine (actress)

Gustav Mahler (composer)

Felix Mendelssohn (composer)

C. Wright Mills (sociologist)

Eugène Minkowski (psychiatrist)

Cole Porter (composer)

Manfred von Richthofen (soldier)

Robert Schumann (composer)

Antonio Vivaldi (composer)

Literature

Hamlet by William Shakespeare

Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare

Vouchsafed into philosophical realms

The historical context in which Philip K. Dick wrote The Simulacra included cold war anxieties, postwar reflections, and the coming-into-being of a mass-media celebrity culture. Marilyn Monroe titillated the nation with her 1962 performance of “Happy Birthday, Mr. President”, then devastated fans with her apparent suicide only 2½ months later. British sociologists and marketers had already begun referring to adulants of heartthrob youth culture as “teenyboppers” when The Beatles released their first album Please Please Me in March 1963 to hysterical reception from young, overwhelmingly female fans. Hannah Arendt’s coverage of the 1961 trial of Adolph Eichmann, printed February through March of 1963, reminded readers of The New Yorker of the inadequate justice of the Nuremberg trials.

Philip K. Dick developed the theme of a simulacrum as a real, potent object with fake characteristics in even small details of his novel, such as the character of Vince Strikerock smoking imitation tobacco. A decade and a half later, the French postmodernist Jean Baudrillard took this tension a step further with his pronouncement: “The simulacrum is never what hides the truth — it is truth that hides the fact that there is none. The simulacrum is true.” Baudrillard proceeded to demonstrate the operation of simulacra by falsely attributing that statement to Ecclesiates on the opening page of his 1981 book Simulacres et Simulation, (translated into English as Simulacra and Simulation in 1983). The quote is nowhere to be found in Ecclesiastes, even with the most radical stretches of creative translation. But Baudrillard’s point was exactly the disorientation produced by the slow disappearance of referential veracity.

There are other points when Baudrillard approximates Philip K. Dick’s use of the term simulacra more closely. In one remarkable simile, Baudrillard directly imitates Philip K. Dick before him by calling androids simulacra: “A whole generation of films is emerging that will be to those one knew what the android is to man: marvelous artifacts, without weakness, pleasing simulacra” [11]. Jean Baudrillard later in his book acknowledged specifically Dick’s novel The Simulacra and certain of its fictional characters [12].

While Philip K. Dick was the first English-language writer to include the word “simulacra” in a book title, it was Baudrillard who vouchsafed simulacra discourse into the mainstream vocabulary via the literary genre of philosophy.

Google n-grams attests to this timeline. A graph tracking the frequency with which the word “simulacra” appeared in print begins its ascent around the time that Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation appeared, while Dick’s The Simulacra did not seem to have inspired as much written interest in simulacra as a concept (at least around the time it was written).

The fact that Baudrillard name-drops Philip K. Dick four times throughout two separate chapters of Simulacra and Simulation hints at the role Dick had to play in shaping the way this concept would come to be understood philosophically.

An illusion of a conclusion

Lucretius translated the proto-scientific physics of Greek philosopher Epicurus into the Latin language. In doing so, Lucretius sought to convey that simulacra were the nearly-imperceptible images that float through the air to produce all manner of unreal, illusory visions, from centaurs to women who look like men.

Jean Baudrillard argued with rigorous detail in Simulacra and Simulation how authentic meaning and cultural memory was becoming mediated and replaced by technological reproducibility. Baudrillard, in that book, credits the science fiction of Philip K. Dick, whose novel The Simulacra had been translated into French eight years prior.

Philip K. Dick fictionalized some of the characteristics of simulacra that Lucretius articulated — in particular, the appearance of familiar people in dreams, erotic obsessions, the uncertain sources of our internal thoughts, and discrepancies between an object and its image. To these modalities, Philip K. Dick, added several novel associations, such as technological reproduction and government mendacity.

Contemporary discourse about simulacra continues, and often preserves these Phildickian influences, even when Philip K. Dick is not considered the source. For example, a later French philosopher, Alain Badiou, wrote in 1993 that Germany’s National Socialist revolution, which ushered the Nazi party into power, was the extreme example of how “Evil is the process of a simulacrum of truth” [13]. Badiou never referenced Philip K. Dick directly; nevertheless, the meticulousness with which Philip K. Dick drew from Nazi political history in The Simulacra (thirty years before Badiou wrote his Ethics) makes the associations between simulacra and the Third Reich an unignorable part of the concept’s development.

Philip K. Dick’s continued relevance can be found in LessWrong discourse during mid-2020, when the concept of simulacra was re-invoked as a description of the less-than-forthrightness with which federal, state, and municipal governments were justifying their responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Debates on whether heavy-handed government policies smacked of misdirection or outright falsehood had distinctly Phildickian resonances, even as such posts tended to overlook Philip K. Dick’s influence on this idea.

“That’s good enough for me, now. I want that, the image; okay?”

— Ian Duncan in The Simulacra

Notes

[0]: Wallace, David Foster. Infinite Jest: A Novel — 20th Anniversary Edition. United Kingdom, Little, Brown, 2016, p.xi. This preface to the Back Bay 20th Anniversary paperback edition was reprinted in The New York Times on February 5th, 2016, with the headline “Inside The New York Times Book Review: David Foster Wallace’s ‘Infinite Jest’.”

[1]: Dick, Philip K. The eye of the sibyl. United Kingdom, Carol Publishing Group, 1992, p.390. The date of the story’s submission is in this book’s endnotes. The short story “Not By Its Cover” itself starts on page 175.

[2]: “Lucretius, de Rerum Natura, BOOK IV, Line 1058.” http://www.perseus.tufts.edu, www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0131%3Abook%3D4%3Acard%3D1058. Accessed 19 Mar. 2023. For a more accessible translation, see also Ronald Melville’s 1997 blank verse translation published by Oxford World’s Classics. Philip K. Dick lauded John Dryden’s abridged 1685 Lucretius translations as “lofty, noble” [1]. While preparing this review, I hunted unsuccessfully for any English translation which left the word simulacra untranslated. The various English translations of De Rerum Natura I found used several different words or phrases within one translation, but among them is almost always the bland phrase “images of things.”

[3]: “EPISTULA I IOANNIS — Nova Vulgata, Novum Testamentum.” http://www.vatican.va, www.vatican.va/archive/bible/nova_vulgata/documents/nova-vulgata_nt_epist-i-ioannis_lt.html. Accessed 19 Mar. 2023. The word simulacra is not used to denote idols anywhere in the books of the Pentateuch, nor in the Gospels. A different Latin term is employed in those books: similitūdō. The books within the Vulgate where the word simulacra is used are the following:

ACTUS APOSTOLORUM

AD COLOSSENSES EPISTULA SANCTI PAULI APOSTOLI

AD CORINTHIOS EPISTULA I SANCTI PAULI APOSTOLI

AD THESSALONICENSES EPISTULA I SANCTI PAULI APOSTOLI

APOCALYPSIS IOANNIS

EPISTULA I IOANNIS

LIBER BARUCH

LIBER ISAIAE

LIBER PRIMUS MACCABAEORUM

LIBER PRIMUS REGUM

LIBER PSALMORUM

LIBER SECUNDUS MACCABAEORUM

LIBER SECUNDUS PARALIPOMENON

PROPHETIA EZECHIELIS

PROPHETIA HABACUC

PROPHETIA OSEE

[4]: Géley, Gustave. From the Unconscious to the Conscious. United Kingdom, William Collins Sons, 1920, p.62. Géley appears to use the word simulacra in Lucretius’ original sense, uncritically accepting De Rerum Natura as a still-reasonably-viable account of experiential phenomenon.

[5]: Harper, George Mills, et al. A Critical Edition of Yeats’ A Vision (1925). N.p., n.p, 1978, p.222. Yeats poetically employs the word only once, in the sense of a spectral ghost. It has been understood to be a misspelling.

[6]: Sutin, Lawrence. Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick. United States, Carol Publishing Group, 1991, p.301. Sutin also suggests that the character of Nicole Thibodeaux was inspired by real-life First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy.

[7]: Dick, Philip K., and Davis, Erik. The Exegesis of Philip K Dick. United States, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011, p.419.

[8]: Dick, Philip K., and Herron, Don. The Selected Letters of Philip K. Dick: 1938–1971. United States, Underwood Books, 1991, p.87. Philip K. Dick’s editor Terry Carr wrote a letter to Philp’s wife Anne. Philip saw the letter and replied to it himself in this letter dated August 13, 1964.

[9]: Dick, Philip. “Novelty Act.” Fantastic, Feb. 1964, pp.8–38. An illustration accompanied this short story, portraying a sculpted bust with a glaring face wearing a periwig. The bottom of the bust had engraved on it the name “J. S. Bach”. On its left and right sides, the sculpture was surrounded by empty moonshine jugs.

[10]: Dick, Philip K. The Simulacra. United States, Mariner Books, 2011, p.19. This excerpt is hardly a spoiler, and, in fact, I hope this review has managed to leave the best parts of the novel’s plot still yet unspoiled.

[11]: Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 1994, p.45. The most notable quote in Simulacra and Simulation succinctly explains Baudrillard’s conception of simulacrum. Baudrillard begins the first chapter of this book (p.1) with an apparent epigram: “The simulacrum is never what hides the truth — -it is truth that hides the fact that there is none. The simulacrum is true.” Baudrillard attributes this quote to “Ecclesiastes.” Nowhere in any translation of the book of Ecclesiastes (including the Latin Vulgate) can one read an even remotely tangential sentiment. This fabricated attribution performatively constructs a simulacrum around a discursive explanation of one.

[12]: Rosa, Jorge Martins. “A Misreading Gone Too Far? Baudrillard Meets Philip K. Dick.” Science Fiction Studies, vol. 35, no. 1, 2008, pp.60–71. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25475106. Accessed 13 Mar. 2023. One of the characters in The Simulacra (Al Miller) possesses a simulacrum of a Martian creature called a papoola. All living papoola have gone extinct. The character Al Miller uses a remote-controllable replica of a papoola to draw in customers to his business. Badrillard writes about the implications of this fictional robot for the field of advertising, but, as Rosa notes, Baudrillard incorrectly spells its name “papula.”

[13]: Badiou, Alain. Ethics: An Essay on the Understanding of Evil. United Kingdom, Verso Books, 2013, p.77. The lineage of simulacra discourse in France appears to have been kindled by an independent re-discovery of Lucretius by Gilles Deleuze, who then influenced Baudrillard. Jorge Rosa (in [12]) suggests that Baudrillard was informed of Philip K. Dick while writing his seminal work, which was more influenced by Deleuze. Alain Badiou also cites Deleuze but not Baudrillard. In fact, Badiou elsewhere hotly dismissed Baudrillard’s significance to philosophy altogether. What I find most interesting in this sequence of events is that every major twentieth-century philosopher who wrote anything about simulacra (with the exception of Philip K. Dick, if one considers him a philosopher, as some do), did so after Philip K. Dick had already written extensively on the topic, not just in The Simulacra, but in other novels as well. These subsequent writers, each of whom made substantial contributions of their own to the discipline of continental philosophy, all spoke French, and they all lived in Paris.

"Baudrillard proceeded to demonstrate the operation of simulacra by falsing attributing that statement to Ecclesiates on the opening page of his 1981 book Simulacres et Simulation"

Falsing should maybe be "falsly".

Good essay.