The Parable of James-James

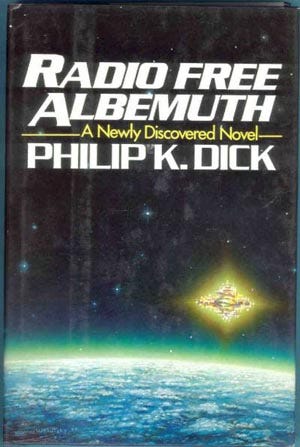

PKD #4: Notes on Radio Free Albemuth by Philip K. Dick

The first novel Philip K. Dick wrote from the aftermath of his religious experiences of 1973, Radio Free Albemuth, was not published during his lifetime. Originally titled Valisystem A, the novel is not included in what Dick would later term his Valis trilogy, the final three novels of his lifetime which fictionalized Dick’s horrifying mystical interactions with some kind of “Vast Active Living Intelligence System” (whose description formed the acronym V.A.L.I.S.).

Like so many other of Dick’s novels, Radio Free Albemuth began as a short story. The theme on which Dick got invited to write an anthology contribution was “fictional authors,” that is “tale[s] supposedly written by an author who is a character in fiction.” The fictional author whom Dick initially chose for this exercise was the novelist character from his 1963 Hugo-Award-winner Man in the High Castle. Dick never submitted that short story “A Man for No Countries” to Philip José Farmer, who had solicited it, but, according to two letters Dick wrote in 1975, it would have shown “Hawthorne Abendsen, the protagonist-author in MAN IN THE HIGH CASTLE, continue on in his difficult life after the Nazi secret police finally got to him.”

By the time Dick wrote that description, he had already built up the short story to novel-length. It was to be “based on my life after Nancy left me, and also based on my ideas about my March experience,” that is, his revelations.

He often referred to his religious experiences as “2-3-74” for February to March 1974, and he developed many theories about their meaning in his “Exegesis” notebook, which he used as novel-notes for this and for all his subsequent novels. As Dick piled on more material from that psychologically complex period of his life, a parallel plotline developed into another novel he told his friends would be titled To Scare the Dead.

In one of the aforementioned letters, to his friend Claudia Bush, he explained “I combine VALISYSTEM A and TO SCARE THE DEAD. Every novel of mine is at least two novels superimposed. This is the origin; this is why they are full of loose ends, but also, it is impossible to predict the outcome, since there is no linear plot as such. It is two novels into a sort of 3-D novel.”

As Dick developed Valisystem A into its first draft, he replaced the fictional author Hawthorne Abendsen with a fictionalized version of himself. Philip Dick is a supporting character in Radio Free Albemuth, which switches first-person perspective from a fictional Philip Dick to his best friend, a record company executive named Nick Brady.

When Dick finished writing Valisystem A in August 1976, Bantam Books agreed to purchase the manuscript on the condition that Dick incorporate several revisions. While Dick agreed to these changes, he never completed the rewrites. Instead, he developed a narratively distinct story over the following two years that Bantam would publish as Valis. In 1985, three years after Dick’s death, Arbor House acquired the rights to Valisystem A, printing the book later that year under the new title Radio Free Albemuth, avoiding any possible confusion with Dick’s 1978 novel Valis.

In Radio Free Albemuth, the character Nick Brady recounts a series of spiritual awakenings which manifest in dreams or waking visions (which appear only during certain hours of the night). He deduces these epiphanies to be external in origin— communications from some helpful being with a way-station in earth’s atmosphere, or floating above it in orbit.

The transmissions received by the fictional Brady spanned many topics, from life-saving medical diagnoses to the secret political agenda of America’s dictatorial President, Ferris F. Fremont. One such transmission concerned the nature and consequences of the divine act of creation:

That night when I went to bed I experienced one of the most vivid dreams so far, one which made a great impression on me.

I found myself watching an enormously powerful scientist at work named James-James; he had wild red hair and flashing eyes and was virtually godlike in the range and scope of his activities. James-James had constructed a machine which chug-chugged and flashed radioactive particles in showers from it as it operated; thousands of people sat about in chairs silently watching as the machine produced first an amorphous living slime and then a rough-cast baby; then, whirling and sparking and thumping, it cast up on the floor before us all a lovely young girl: pinnacle of perfection in the cosmic process of evolution.

Beside me in the dream, my wife, Rachel, rose from her seat, wishing to see better what James-James had accomplished. Immediately filled with rage at her audacity in standing up, James-James seized her and threw her to the floor, splintering her kneecaps and her elbows in his fury. At once I stood upright in protest; I moved down the stairs towards James-James, calling on the rows of silent people to complain. There then moved into this large assembly hall men in greenish-brown khaki uniforms, on motorcycles, carrying with them as they rapidly and smoothly advanced the emblems of Rommel’s Afrika Korps: the sign of the palm tree.

To elaborate, Erwin Rommel commanded an expeditionary force for Nazi Germany into Egypt and the Maghreb between 1940 and 1943. His troops’ palm tree insignia had no background details. Superimposed on the palm tree design was the swastika.

In an earlier scene of the novel, the speaker in this passage, Nick Brady, saw a vivid dream of palm trees, indicating, he came eventually to realize, that he should move to Orange County, California.

Dick (the real one) experienced his own vision of a palm tree garden in 1974 or 1975, which he found various interpretations for as he revisited the experience over time.

To them I croaked in hoarse appeal, “We need medical assistance!” As the dream ended, the first scouts of the invading, rescuing Afrika Korps heard me and turned toward me, with fine, noble faces. They were dark-skinned men, rather small and delicate, a race apart from James-James, with his too-pale skin and bright red hair. Their eyes were large, gentle and expressive, dark; they were, I realized, the vanguard of the King.

Dick doesn’t address in the dream’s interpretation or elsewhere in the book that the protagonist here calls upon Nazi soldiers for aid, men described as “fine” and “noble” in appearance. While many other of Dick’s novels evince his extensive knowledge on the history of the third reich, Radio Free Albemuth makes no other allusions to Germany’s wartime cadres. As Brady, the dreamer, states immediately afterwards, the image unsettles him.

Waking up from this disturbing dream, I sat by myself in the living room; the time was about 3:00 a.m. and the apartment was totally silent. The dream suggested a limitation to what James-James—who was Valis—could do for us, or rather would do; that his power was in fact even dangerous to us if misused. It was to the rightful King that we would have to turn for ultimate help, expressed in the dream as “medical assistance,” the thing we most needed in order to repair the damage done by the historical, evolutionary process that the original creator James-James had set in motion. The King was a correcting agent against the abuses of that temporal process; powerful and heroic as it was, it had claimed innocent victims. Those victims, at least eventually, would be healed by the legions of the rightful King; until he arrived, I realized, we would receive no such help.

Who is this rightful King? Dick’s own Episcopalian background and the strong religious tenor of the novel’s context suggests a trinitarian relationship: James-James as God-the-Father and the King as God-the-Son. On the other hand, the phrase “until he arrived” suggests one who is still much awaited-for but has not yet come.

How is it “the vanguard of the King,” if he is a “rightful King,” should include a Panzer division of Hitler’s Wehrmacht? Surely Dick could not have been suggesting that Erwin Rommel, one of the top generals of the German Reich, espoused the spirit of this King?

This Erwin Rommel (1891-1944), known popularly in his fatherland as “der Wüstenfuchs” (The Desert Fox) was executed in October 1944, coerced to ingest cyanide by Gestapo investigators who found him complicit in a coup d’état attempt which failed to depose Hitler. While historians have debated the extent of Rommel’s actual involvement in the assassination attempt of 20 July 1944, Rommel’s death, revealed only after the war to be an execution, could symbolize in this novel the disgrace, up to and including the murder, faced by those who throughout history sought to destabilize despotic governments. The unjust demise of those fighting to undermine tyranny forms a major theme in Radio Free Albemuth.

Radioactive particles, I thought—remembering the rapid-fire emission of bits of light from James-James’s cosmic machine—like you find in cobalt therapy. The double-edge sword of creation: radioactivity in the form of cobalt bombardment cures cancer, but radioactive emissions are themselves cancer-producing. James-James’s cosmic machine got out of hand and injured Rachel, who stepped out of line in the sense that she stood up. That was enough to enrage the cosmic lord of creation. We need a defender as well. An advocate on our side, who can intervene.

It should not surprise anyone that the experience of beholding the dream-form of James-James as the terrifying creator was not really fictional. In another letter to Claudia Bush, dated 21 March 1975, Dick shared similar details of his truly lived James-James dream, which formed the basis for the above excerpt. He wrote her: “The dream about James-James certainly expressed what I saw in 3-74: with the Creator producing first solar flares (or the atom and its moving parts), then from it the baby, and then evolving from the baby Kathy. But that he had to injure Tessa (because she stood up to see his “act” better)—this was what I saw as an objection to linear forward moving time and continual creation anyhow: that in the powerful huge surging-forward drive of life, so many creatures are wounded and crippled, left to die, behind the flock. And in my dream I asked for help, and none of the thousands sitting around to form an attentive audience for James-James would lift a finger, despite my appeals. But then the wide glass doors opened, and the first scouts entered the great building. ‘We need medical assistance,’ I said to them, and they came toward me; small as they were, and only the first vanguard, they did represent another force, one which heard and responded.”

The “Tessa” referred to in this letter was Philip’s spouse during this time, his fifth wife (please share a comment if you know who “Kathy” refers to).

Philip K. Dick continued writing about this dream character James-James in his Exegesis notes well after he submitted to his agent what would be the final manuscript for Radio Free Albemuth. The significance of the name James (a Hellenization of the Hebrew name Jacob) isn’t expanded upon, nor is the significance of its reduplication (linguistic iconicity, perhaps). The given details of his red hair and too-pale skin remain mysterious as well.

This dream of James-James does not appear in any other novel, but the James-James character did appear in at least one more of Dick’s dreams. In November or December of 1976, Dick wrote: “A new James-James dream: the improvident genius creator evolves us through many stages, meanwhile killing us, coercing us totally, injuring us. Finally, really through lack of foresight (he has no foresight) he abruptly, in his truly inspired search for new and more complex and evolved forms for us to take, causes us to become immortal gods; we all float up from the ground, high in the air, singing in unison like a great chorus of bees: he has caused us to escape him and the death of determinism and suffering, due to a combination of his genius, restless, ceaseless inventiveness and search for new or better forms—and lack of foresight; it didn’t occur to him that by his own efforts he would eventually, inevitably push us to safety. We are filled with joy. The inference here seems to be that on his own, James-James can and eventually will make us immortal and no longer bound by determinism (expressed by our release from gravity), hence safe from him.”

Many other notes on James-James appear in Dick’s letters and journals, such as one making the accusation, “For exposing his world James-James is after your ass. The authorities are his instruments in forcibly maintaining the system of delusions.” In another Exegesis excerpt, Dick comes to the realization, “our God (Christ) has wisdom and knows just how to arrange everything which James-James grinds out.”

Back to the dream-passage in this novel:

Cancer… the process of creation gone wild, I thought. And then, in an instant, the AI operator transferred an explanation to my mind; I saw James-James the creator as master of all prior or efficient causes, of the deterministic process moving forward up the manifold of linear time, from the first nanosecond of the universe to its last; but I also saw another creative being at the far end of the universe, at its point of completion, directing, accepting, shaping, and guiding the flow of change, so that it reached the proper conclusion. This creative entity, possessing absolute wisdom, guided rather than coerced, arranged rather than created; she or it was the architect of the plan and the controller of final or teleological causes. It was as if the original creator of the universe lobbed it like a great softball on a long blind trajectory, whereupon the receiving entity corrected its course and led it right into her glove. Without her, I realized, the great softball which was the universe—however well and hard it had been thrown—would have wandered out into left field somewhere and come to rest at some random, unpremeditated spot.

To speak from the vantage point of Philip K. Dick’s cosmology, the ultimate creator has a distinct personality. He is not an accretion of impassive laws or random physical forces. He is wise, in the sense that an engineer is wise, creating these technologically advanced inventions, but with no regard for how they will be used. The creator permits suffering, and even inflicts it. Emanations which are outside his purview include:

Relief

Sympathy

Foreknowledge

Truth

Justice

Such virtues are relegated to the discretion of those less skilled than the creator (or perhaps less busy). Within this one dream, these people included:

The rightful King (whomever that indicates)

The man in the audience crying for medical attention (Dick himself at first, but in the story Nick Brady, and perhaps anyone who calls attention to the agonies of the defenseless)

The field marshal who tried to assassinate a tyrant (even if the attempt was, in the end, unsuccessful)

The foot-soldiers of incident response (but only the vanguard portion of them)

In his own private notes on this dream, Dick refers to what Brady knows as the Afrika Korps as “the PTG task force,” an abbreviation for Palm Tree Garden. As late as 1978, he wrote: “In the James-James dream I saw the PTG task force arriving silently & swiftly. So they must be close by, now. But to say ‘now’ is to fall into the delusion of regarding linear time as real. They could be seconds away.”

Radio Free Albemuth continues its dream interpretation:

This dialectic structure of the change process of the universe was something I had never glimpsed before. We had an active creator and a wise receiver of what he created; this did not fit any cosmology or theology I had ever heard of. The creator, standing before the creation, his creation, had absolute power, but from my James-James dream I could see that in a very real sense he lacked a kind of knowledge, a certain vital foresight. This was supplied by his weak but absolutely wise counter-player at the far end; together they performed in tandem, a god, perhaps divided into two portions, split off from himself, so as to set up the dynamics of a kind of two-person game. Their goal was the same, however; no matter how much they might seem to conflict or work against each other, they commonly desired the successful outcome of their joint enterprise. I had no doubt, therefore, that these twin entities were manifestations of a single substance, projected to different points in time, with different attributes predominating. The first creator predominated in power, the final one in wisdom. And in addition there was the rightful King, who at any time could breach the temporal process at some point of his selection and, with his hosts, enter creation.

This image of the creator reminds me of the conception of God that gave rise to one nickname for the Higgs Boson, a subatomic particle confirmed to exist in 2013 based on evidence gathered at the Large Hadron Collider. While Dick elsewhere developed his own theories around tachyon particles, the boson was not a particle over which he spilled any ink. A controversial nickname arose for the Higgs Boson in order to suggest the mechanism by which it operates, bestowing mass on all other fundamental particles: physicist Leon Lederman dubbed it the “God particle.”

James-James continuously creates, but the mitigating forces that handle these creations belong to other, separate cosmic benevolences— to “the King,” but also to “the wise receiver”. Each of these distinct personalities has a role differentiated by function and by position in time.

Like cancer cells, the original constituents of the universe proliferated without direction, a total panoply of newness. Allowed to escape, they went wherever causal chains drove them. The architect who imposed form and order and deliberate shape was, in the cancer process, somehow missing. I had learned a great deal from my James-James dream; I could see that blind creation, not subjected to pattern, could destroy; it could be a steamroller that crushed the small and helpless in its eagerness to grow. More accurately, it was like one immense living organism which spread out into all the space available to it, without regard for the consequences; it was only impelled by the drive to expand and increase. What became of it largely depended on the wise receiver, who pruned and trimmed it as each step of the growth took place.

A Freudian maxim of dream interpretation states the dreamer is all characters in his dream. And, in fact, we can find this dimension of the James-James dream in Dick’s later (post-Radio Free Albemuth) analysis of this dream. In an entry from the Exegesis dated to June or July 1978, Dick wrote, “The mad God James-James began generating world upon world, worlds unrelated, worlds within worlds. Fake worlds, fake fake worlds, cunning simulations of worlds, mirror opposites of worlds. Like I do in my stories and novels (e.g., Stigmata and ‘Precious Artifact’). I am James-James.”

In part, Radio Free Albemuth is an anti-totalitarian political allegory, exaggerating the Stasi-like surveillance apparatus during America’s Nixon era. The delusional President Ferris F. Fremont clearly stands in for President Richard M. Nixon. In a radio interview from either 1977 or 1979, Dick said, “My fears became greater during the Nixon administration because at that time there really was some basis for people like me to worry. After Nixon was deposed my fears went away completely.”

It’s also a novel of religious speculation, examining the implications of a cosmic intelligence superior to our own who shapes world history by teaching esoteric knowledge to sensitive idealists oppressed by Empire.

The selection above outlines the Gnostic demiurge of Dick’s cosmology, a masterful builder who passes over whatever needs his creatures feel in favor of filling the universe, making it stronger and stranger. While the name James-James appears only in this novel (in its eighteenth chapter), Dick would continue to write about James-James’s attributes for years later. Mitigating the most deleterious effects of the divine prerogative—that is, of creation itself— requires some kind of a wise system for our behalf, some method of arranging the after-effects of creation in ways that take human interests into account. The consequences of our universe existing at all must be guided so that his creative detriti fall into patterns protecting the unique needs of human beings. While the identity of who shall do this is not made entirely clear in the novel, the answer perhaps is everyone who seeks to give voice to the victims of injustice (other of the novel’s passages flesh out this theme).

A note in Philip K. Dick’s Exegesis from March 1978 reaches the conclusion: “James-James certainly was deranged, and it certainly was this world he was spinning out.”