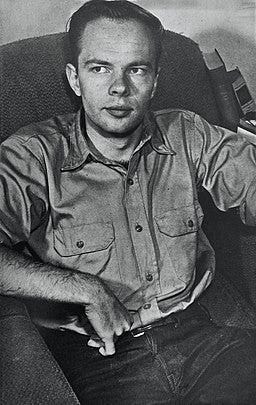

By 1964, science-fiction author Philip K. Dick had won the “Hugo Award for Best Novel” for his novel The Man in the High Castle, which he published two years earlier. In the year of 1964, Dick completed his thirty-second novel, The Penultimate Truth.

In The Penultimate Truth, Dick imaginatively described a remarkable technology in the world of his story, one which bears noticeable similarities to ChatGPT, the viral AI tool recently launched by OpenAI.

Philip Dick died in 1982, forty years before the first release of ChatGPT in 2022. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has never specifically mentioned the influence of Philip Dick on any of his entrepreneurial ventures or his engineering interests.

Nevertheless, it’s conceivable that Philip K. Dick’s plethora of speculative fiction, often containing tropes of intelligent machines and man’s relation to them, influenced the direction of artificial intelligence research, particularly during the many years since his work gained mainstream popularity.

In The Penultimate Truth, the character Joe Adams, a speechwriter, employs a tool that Dick calls a “rhetorizer” to aid in his job responsibilities as a wordsmith. Much like ChatGPT, the rhetorizer requires a human to enter a text prompt, and based on that input, it produces well-formed sentences in response.

This speechwriting character in Dick’s story finds that the “rhetorizer”, much like ChatGPT, can produce unsatisfactory results, when it is fed only a meager prompt to work with (a funny excerpt is reproduced at the end of this blog post).

Like many ChatGPT users are discovering today, Dick’s character Joe Adams finds that some “prompt engineering” can push his paragraph-producing assistant in more helpful directions; in the story, he even tests the tool’s limits with some nonsense prompts.

The fictional machine known as a rhetorizer is introduced early in The Penultimate Truth, and it plays some role in the plot, which I will not spoil here.

Philip Dick thoughtfully considered some of the implications of having machines generate our words for us. It’s worth looking to science fiction, and to The Penultimate Truth in particular, for lessons that we can bear in mind as the far-fetched technologies of yesterday’s pulp novels materialize in the reality of today.

Below, I’ve tried to distill some of the implications suggested by the “rhetorizer” passages in Dick’s The Penultimate Truth.

Longer prompts can produce more precise results.

A human still has to know what point to get across before a machine can successfully spell it out.

Reliance on a machine for your linguistic productions can lead to dependency, or even a loss of independent ability.

There’s no replacement sometimes for writing your own words.

I’ve reproduced below a selection from Chapter 1 of The Penultimate Truth, containing a scene showing how the “rhetorizer” works.

[…]

Some questions come to mind as we examine the similarities between Philip Dick’s rhetorizer and today’s deep-learning language models such as ChatGPT:

Did Philip K. Dick prophetically predict the use of large language models?

Can over-reliance on language-producing machines make us so “hooked” that we struggle to come up with our own words?

Or, is ChatGPT so dissimilar from the “rhetorizer” machine that Philip Dick described in 1964 that it fails to bear meaningful relevance to the large language models of today?

What do you think?

Excerpts from The Penultimate Truth are under copyright. To read more, buy the book.

Dick, P. K. (2012). The Penultimate Truth. United States: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.